2 The Bi-Dimensional Rejection Taxonomy

This chapter has been published as, Sunami, N., Nadzan, M. A., & Jaremka, L. M. (2019). The bi‐dimensional rejection taxonomy: Organizing responses to interpersonal rejection along antisocial–prosocial and engaged–disengaged dimensions. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12497.

Responses to interpersonal rejection vary widely in form and function. Existing theories of interpersonal rejection have exclusively focused on organizing these responses on a single antisocial–prosocial dimension. Accumulating evidence suggests a gap in this approach: variability in social responses to rejection cannot solely be explained by the antisocial–prosocial dimension alone. To fill this gap, we propose the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy, consisting of the antisocial–prosocial x-axis and engaged-disengaged y-axis, a novel contribution to the literature. We demonstrate that both the x- and y-axes are necessary for understanding interpersonal responses to rejection and avoiding erroneous conclusions. We also show how this new framework allows researchers to generate more nuanced and accurate hypotheses about how people respond when rejected. We further demonstrate how existing research about individual differences and situational factors that predict responses to rejection can be viewed in a new light within the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy. We conclude by suggesting how the taxonomy inspires innovative questions for future research.

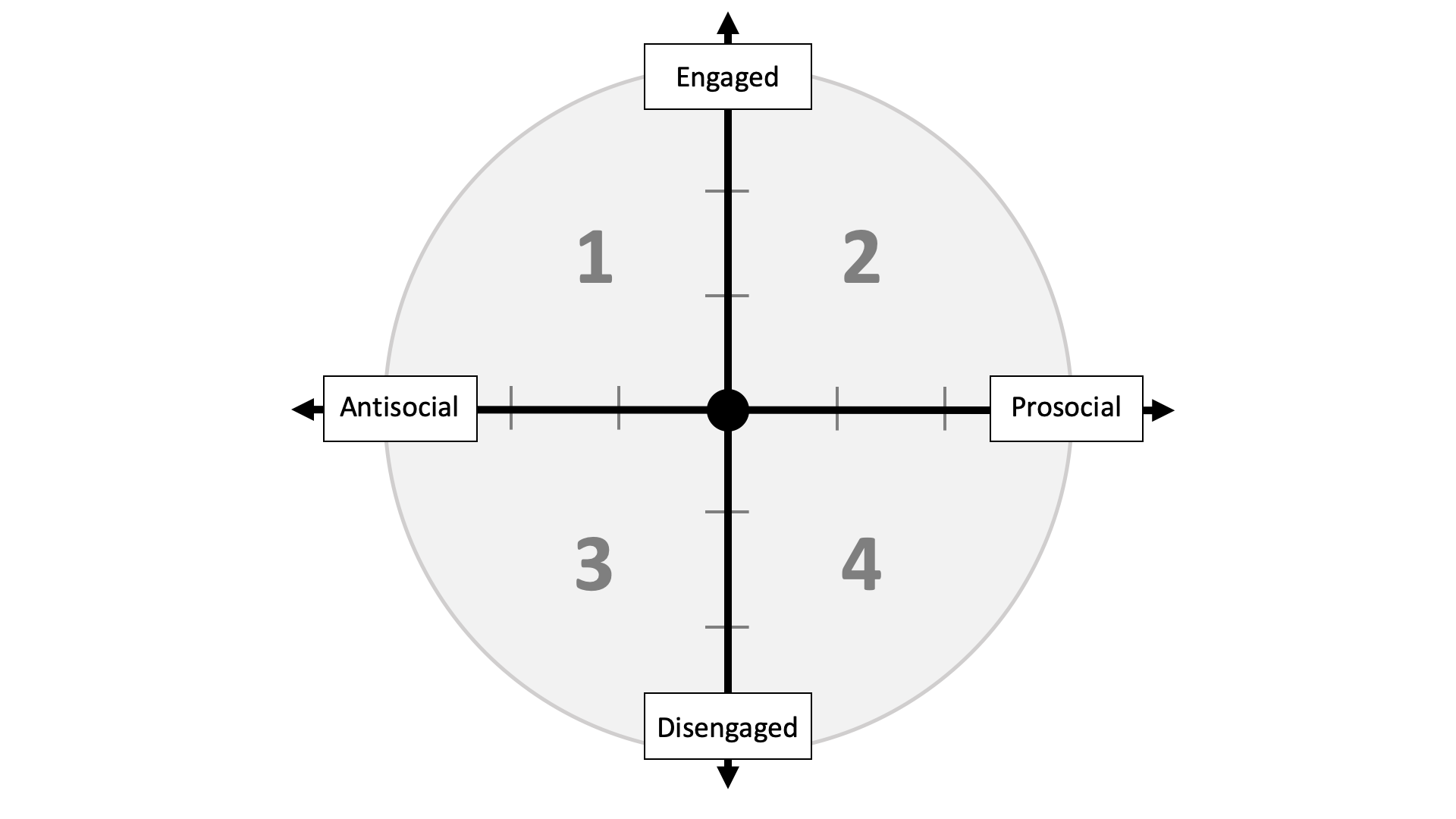

Traveling with an incomplete map is not very efficient—a traveler may end up in the wrong place because they are unsure where they are going. This analogy can also be applied to scientific research—a researcher is likely to arrive at an incorrect conclusion because they are using an incomplete theoretical framework. In this paper, we suggest that the rejection literature is operating with an incomplete theoretical framework for understanding responses to interpersonal rejection. Existing theories have already advanced our understanding of how people respond to rejection, primarily focusing on a single antisocial–prosocial dimension. Although this dimension is important, we suggest that not all antisocial and prosocial responses are identical. To account for this unexplained variability, we incorporate a second dimension, the engaged–disengaged dimension, adopted from the coping literature (Carver and Connor-Smith 2010; Dijkstra and Homan 2016). Accordingly, we propose the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy, consisting of an antisocial–prosocial x-axis and an engaged–disengaged y-axis (Figure 2.1). Adding this second dimension provides a more thorough theoretical framework for understanding responses to rejection, equipping researchers with a more complete map for generating new hypotheses.

Our new taxonomy benefits the rejection literature in three ways. First, it provides a unified map for researchers to organize belonging-relevant responses to interpersonal rejection. Without this map, researchers would solely rely on the antisocial–prosocial x-axis, leading to inaccurate conclusions about rejection-elicited responses, as highlighted throughout the paper. For example, if a researcher only assessed engaged prosocial responses to rejection, and rejected participants didn’t preferentially display these responses, the researcher might erroneously conclude that rejection doesn’t lead to prosocial responses at all. Using the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy, we can see that rejected participants could still display prosocial behavior, but in a disengaged manner. Thus, the engaged–disengaged y-axis of the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy creates a cohesive framework, preventing researchers from reaching inaccurate conclusions about rejection-elicited responses.

Second, having a bi-dimensional framework allows researchers to generate more nuanced and accurate predictions about responses to rejection. In the past, researchers focused exclusively on how rejection affected antisocial and prosocial behavior (the x-axis) without differentiating types of behavior within these categories. As a result, existing hypotheses were limited in specificity. With the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy, researchers can generate more nuanced and innovative hypotheses that incorporate both the antisocial–prosocial x-axis and the engaged–disengaged y-axis. For example, without the taxonomy, a researcher might hypothesize that both Situation A and Situation B lead to prosocial responses following rejection. However, with the new taxonomy, researchers can hypothesize that Situation A leads to engaged prosocial responses (e.g., reaching out to close others for connection), whereas Situation B leads to disengaged prosocial responses (e.g., watching their favorite TV program to feel socially connected). This hypothesis highlights potential differences between Situation A and B that would not be apparent without the taxonomy. Thus, the taxonomy arms researchers with a comprehensive framework of potential response options. Researchers can then use existing theoretical and empirical work to generate more nuanced and accurate hypotheses.

Third, the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy highlights types of responses that are understudied in the rejection literature. As we discuss later, the bulk of rejection research has focused on engaged antisocial and prosocial responses. Using the lens of the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy, we can see that many disengaged responses are yet to be examined in the context of rejection, highlighting the need for further research.

In proposing the taxonomy, we rely on existing work demonstrating that self-protective and belonging needs are fundamental to human nature, and that interpersonal rejection threatens these needs, motivating behavioral responses (Baumeister and Leary 1995; Maslow 1943; Murray et al. 2008; Richman and Leary 2009; Williams 2009). Throughout this paper, we use interpersonal rejection as an overarching phrase that encompasses threats to belonging, including social exclusion, social rejection, ostracism, and relational devaluation—referring to experiences when a person feels like they aren’t loved, cared for, or accepted (Leary et al. 1995). 1

We exclusively focus on responses to rejection that are purposeful and voluntary (in contrast to automatic and involuntary responses) since our goal is to describe how people cope with rejection. This focus is consistent with the coping literature (on which the y-axis is heavily based) that defines coping as purposeful and conscious attempts to deal with the stressor (Connor-Smith et al. 2000). Automatic or involuntary responses (e.g., attentional bias to smiling faces) are outside the scope of the taxonomy and thus outside the scope of this paper.

We divide the current paper into two parts. In the first half, we review previous research supporting the antisocial–prosocial x-axis and introduce a novel engaged–disengaged y-axis. In the second half, we highlight how the taxonomy allows researchers to see existing published work through a new lens and discuss new directions for future research.

2.2 A New Dimension: The Engaged–Disengaged y-Axis

A close inspection of existing empirical work reveals that there is significant variability within antisocial and prosocial responses—reflecting heterogeneous strategies for responding to interpersonal rejection. For example, prior research demonstrated that rejection sometimes leads to direct and active attempts to connect with others [e.g., spending money to garner acceptance from others; Maner et al. (2007); Romero-Canyas et al. (2010)]. At other times, rejection leads to indirect and passive attempts to connect with others [e.g., experiencing nostalgia; Derrick, Gabriel, and Hugenberg (2009)]. No existing theories of interpersonal rejection can distinguish between these varied responses—both types of responses are categorized as prosocial in the context of existing theories. The bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy makes a novel claim that the antisocial–prosocial x-axis captures only one dimension of responses, and that a new dimension is needed to fully understand responses to rejection. In this section, we first review foundational theories that suggest an additional possible dimension. Then, we define our new engaged–disengaged y-axis at the end of this section.

2.2.1 Foundational Theories

To understand the variation within antisocial and prosocial responses, we rely on theoretical and empirical work in the coping literature. This extensive literature describes the ways in which people cope with (i.e., voluntarily and purposefully respond to) stressors; thus, this literature provides a rich foundation for building our y-axis.

Coping researchers have proposed various ways to classify coping responses, including emotion-focused, problem-focused, proactive, and meaning-focused coping (Aspinwall and Taylor 1997; Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Skinner et al. 2003). Using factor analyses and theoretical discussions, researchers identified an engaged–disengaged dimension as the critical factor underlying the majority of coping responses (Carver and Connor-Smith 2010; Compas et al. 1997; Connor-Smith et al. 2000; Dijkstra and Homan 2016; Scheier, Weintraub, and Carver 1986; Skinner et al. 2003; Tobin et al. 1989). According to this literature, engaged coping strategies are direct and active behaviors that confront the stressor with a “hands-on” approach. A person has used an engaged coping strategy when they act out their frustrations on others (e.g., aggression), seek social support, or behave in other active and direct ways (Carver and Connor-Smith 2010; Dijkstra and Homan 2016). On the other hand, disengaged coping strategies refer to indirect and passive behaviors that aim to avoid the stressor. Examples of disengaged coping are social withdrawal, denial, and wishful thinking (Carver and Connor-Smith 2010).

We can easily apply the distinction between engaged and disengaged coping to understand how people respond to interpersonal rejection. In the context of rejection, the stressor that people are coping with is the threat to belonging and self-protection/control experienced by the rejected person. As noted earlier, these need-threats are well-documented consequences of experiencing rejection (Williams 2009). The threats to belonging or self-protection/control can be present-oriented, when a person is trying to cope with the current need-threat, or it can be future-oriented, when a person is trying to pre-emptively cope with a potential future need-threat. In coping with those stressors, people can respond in ways that are more engaged versus disengaged. We adopt these ideas in defining the y-axis, as described in the next section.

Although no past theories have explicitly differentiated responses to rejection as engaged or disengaged, some researchers have implied the existence of this distinction by separating social withdrawal from other antisocial responses. For example, the multimotive model identifies social withdrawal as a subtype of antisocial (belonging-diminishing) responses that are separate from more overt antisocial responses such as aggression (Richman and Leary 2009). Attachment theory also differentiated social withdrawal from other overt forms of behavior (e.g., aggression) as a response to prolonged rejection from an attachment figure (Bowlby 2000; Horney 1964). These theories both support the distinction proposed by the coping literature: disengaged antisocial responses are different from engaged antisocial responses. As we describe later, a benefit of formally defining the engaged–disengaged y-axis is that it highlights additional forms of disengaged antisocial responses that have been neglected by existing theories.

Another theory that supports differentiating antisocial and prosocial responses is the investment model, a widely-used theoretical model in the romantic relationships literature. The investment model uses a two-dimensional space, characterizing how romantic partners behave when their romantic relationship is in decline (Rusbult, Zembrodt, and Gunn 1982; Rusbult and Verette 1991; Rusbult 1987). Specifically, the investment model proposes the destructive–constructive dimension (similar to our antisocial–prosocial x-axis, as described previously) and the active–passive dimension (similar to, but also different from, our engaged–disengaged y-axis). Before discussing similarities and differences between the multimotive model, the investment model, and our new taxonomy, we first define the disengaged–engaged y-axis so that the reader has a complete understanding of these terms. Then, in the following section, we discuss how our model contributes over and above existing work in advancing our understanding of responses to interpersonal rejection.

2.2.2 Defining Engaged–Disengaged Responses to Rejection

Based on the literature reviewed above, we propose the engaged–disengaged y-axis that describes whether a response to rejection represents an engaged or disengaged attempt to cope with the stressor. Again, the stressor in the context of rejection is the current or future need-threat [i.e., the threat to self-protection/control or affiliation needs; Baumeister and Leary (1995); Williams (2009)]. We define engaged responses as direct and active attempts to deal with the stressor. They are “hands-on”, approach-based strategies to confront and face the stressor. An example of an engaged antisocial response is behaving aggressively towards one’s romantic partner, because exerting control over one’s partner actively and directly replenishes the sense of self-protection/control thwarted by rejection. An example of an engaged prosocial response is seeking support from a loved one because this response actively and directly replenishes the sense of belonging thwarted by rejection (Murray et al. 2008, 2002).

In contrast, we define disengaged responses as indirect and passive attempts to handle the stressor. They are “hands-off”, avoidance-based strategies to evade and divert from the stressor. These responses help to avoid threats to belonging or self-protection/control. An example of a disengaged antisocial response is social withdrawal, because withdrawing is a hands-off strategy that allows a person to avoid further rejection (and thus further threats to belonging or self-protection/control). An example of a disengaged prosocial response is relying on social surrogates (e.g., parasocial relationships)—such as watching one’s favorite TV show or passively browsing social media to obtain social connection. This qualifies as disengaged because social surrogates allow people to passively and indirectly replenish belonging while avoiding future rejection.

Importantly, the engaged–disengaged y-axis is defined by whether the response itself is engaged (direct, active, hands-on) or disengaged (indirect, passive, hands-off); it is not defined by the situation or environment in which it occurs. At the same time, recognizing the situation in which the response occurs is important because the situation limits possible response options. In a person’s day-to-day life, there is often a lot of flexibility in responding. For example, a rejected person can choose whether to seek social support (an engaged response) or watch their favorite TV show (a disengaged response) even if they are in the same situation (e.g., at home with their romantic partner on a Friday after work). This response flexibility is usually absent among lab studies where participants are given only one option to respond (e.g., participating in a noise blast task and deciding how much noise to blast, but not being given any other response options). Thus, the situation has the potential to constrain responses to be either engaged or disengaged, especially in laboratory studies. Using the engaged–disengaged y-axis, researchers can design studies that include diverse response options, as we highlight in the future directions section towards the end of the paper.

Together with the antisocial–prosocial x-axis, the engaged–disengaged y-axis completes the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy. These two dimensions both describe the function of a given response: whether a response functions to reduce or promote connection (x-axis) and whether a response functions as a direct, active, hands-on way of coping versus an indirect, passive, hands-off way of coping with the stressor (y-axis). In the next section, we discuss how the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy compares with the existing theories of social behavior. Then, we provide examples of responses within each quadrant, demonstrating how the two dimensions are independent from each other.

2.3 Comparisons with Existing Theories

The bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy provides a novel lens through which to view responses to rejection, incorporating both the antisocial–prosocial and engaged–disengaged dimensions. How does the taxonomy compare with other theories? In this section, we discuss the advantages of the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy over existing theories in the rejection and close relationships literatures.

Compared with existing rejection theories, the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy provides a more nuanced and accurate depiction of responses to interpersonal rejection. The main advantage of the taxonomy is its power to differentiate engaged and disengaged responses, particularly prosocial responses. Past literature showed that rejected people respond in ways that qualify as disengaged and prosocial, such as thinking about one’s favorite TV program (e.g., Derrick, Gabriel, and Hugenberg 2009) and that people can fulfill belonging in a variety of ways, including via social surrogates [e.g., a fictional character; Gabriel and Valenti (2017)]. However, no existing theories have formally differentiated these types of prosocial responses from other more engaged responses (e.g., seeking social support from a loved one; Murray et al., 2008). The bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy also differentiates disengaged antisocial responses. Among disengaged responses, social withdrawal is the only form of disengaged antisocial responses currently described by existing rejection theories, such as the multimotive model (Richman and Leary 2009). With the current taxonomy, we can see that there are additional types of disengaged antisocial responses not described by the multimotive model or any other existing theory (e.g., passive aggressive behavior, as we describe in detail later). The bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy thus accounts for more responses than any other framework available in the rejection literature.

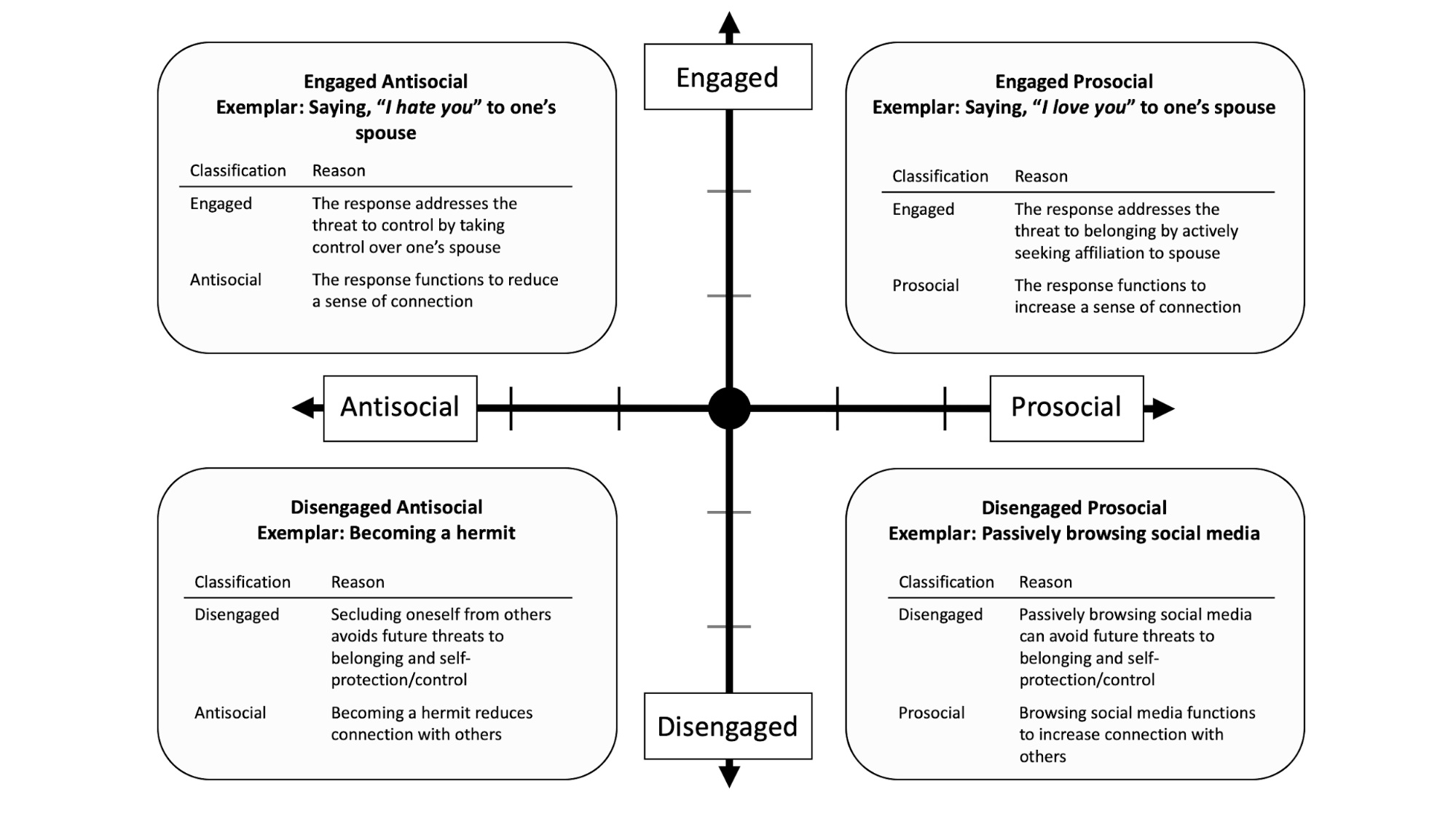

The bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy also offers advantages over the investment model in the close relationships literature. The investment model suggests that responses to romantic relationship decline range along a two-dimensional space: the destructive–constructive (i.e., how a response damages or nurtures the romantic relationship) and active–passive (i.e., how a response overtly or indirectly affects the romantic relationship) dimensions (Rusbult, Zembrodt, and Gunn 1982). On the surface, the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy seems similar to the investment model. However, the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy is more advantageous than the investment model in considering broader sources of rejection and targets of the response. The investment model characterizes situations when the romantic relationship partner is the source of relationship decline, and it only characterizes responses towards an existing relationship partner (Rusbult, Zembrodt, and Gunn 1982). The bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy captures threats to belonging from any source while also characterizing responses towards any target, not just the romantic partner. Finally, the engaged-disengaged y-axis of the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy more accurately captures variation among antisocial and prosocial responses evident in the rejection literature. Whereas saying “I hate you” to one’s partner is a passive response (on the bottom half of the y-axis) according to the investment model (Rusbult, Zembrodt, and Gunn 1982), this behavior would quality as engaged (on the top half of the y-axis) according to the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy. The y-axis of the taxonomy is founded on decades of work in the coping literature (Carver and Connor-Smith 2010; Compas et al. 1997; Connor-Smith et al. 2000; Dijkstra and Homan 2016; Scheier, Weintraub, and Carver 1986; Skinner et al. 2003; Tobin et al. 1989), and is also consistent with the way existing rejection research classifies responses (Richman and Leary 2009).

2.4 Plotting Existing Studies in a Bi-Dimensional Space

In the previous sections, we reviewed literature supporting the antisocial–prosocial x-axis and introduced the engaged-disengaged y-axis to the rejection literature. We also compared this taxonomy with existing theories, and demonstrated that the taxonomy presents many advantages. In this section, we discuss select evidence demonstrating that interpersonal responses to rejection can be plotted in this two-dimensional space, broadly categorized into four quadrants: engaged antisocial responses (Quadrant 1), engaged prosocial responses (Quadrant 2), disengaged antisocial responses (Quadrant 3), and disengaged prosocial responses (Quadrant 4). We present a hypothetical exemplar for each dimension in Figure 2.2 to illustrate the differences among quadrants and help the reader understand each quadrant. We also discuss existing research that falls into each quadrant in this section. Since no past studies included both of these new dimensions in their studies, we infer which quadrant a response falls into based on the properties of the response. We begin by reviewing existing empirical work that falls into Quadrant 1, and then move to Quadrants 2, 3, and 4.

The bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy highlights types of responses that have been understudied in the literature (e.g., passive aggressive behavior and nostalgia). To better illustrate these new kinds of responses, we discuss multiple examples for Quadrants 3 and 4 (i.e., disengaged antisocial and prosocial responses). Since past literature has extensively discussed responses in Quadrant 1 and Quadrant 2 (i.e., engaged antisocial and prosocial responses, as discussed above), we highlight only one representative example for these quadrants.

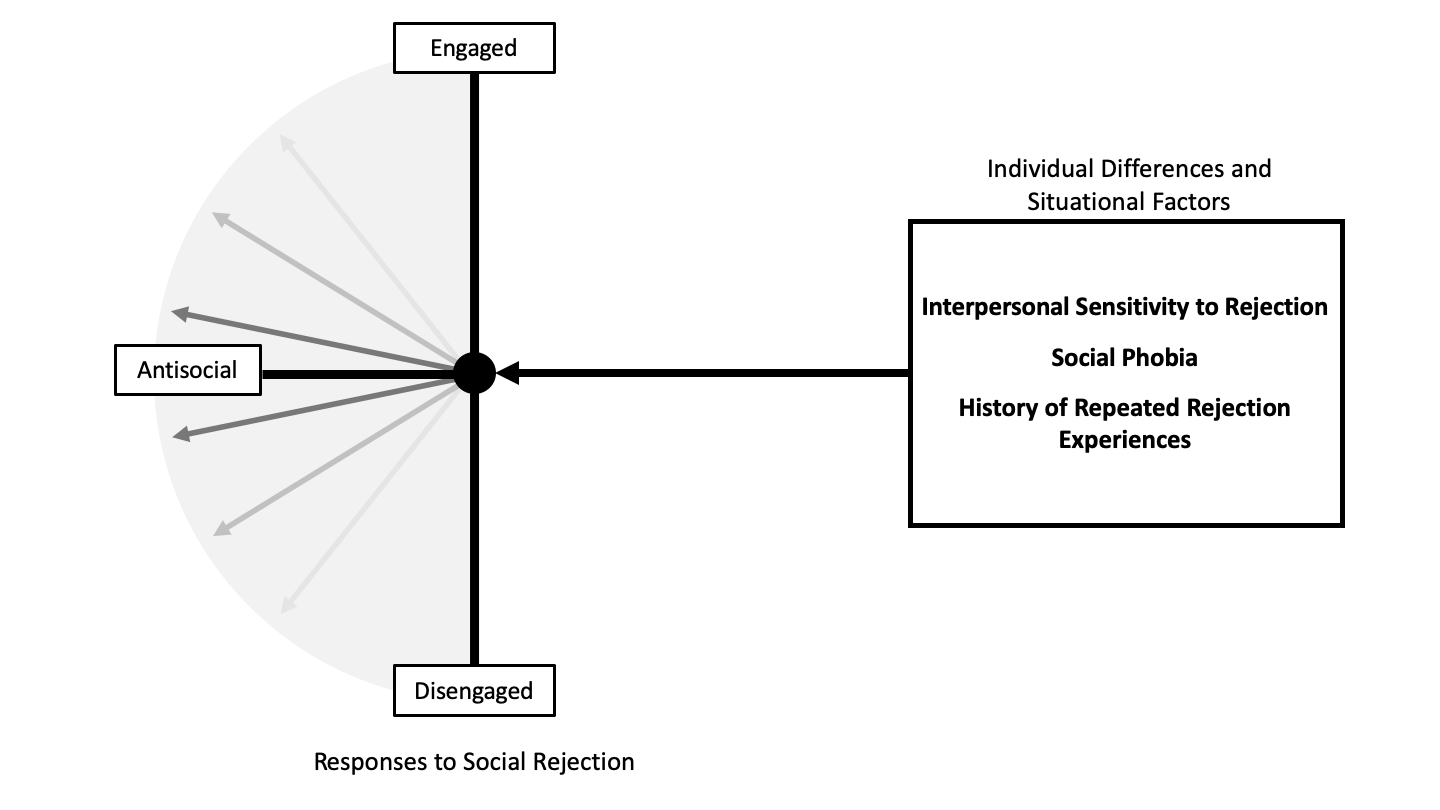

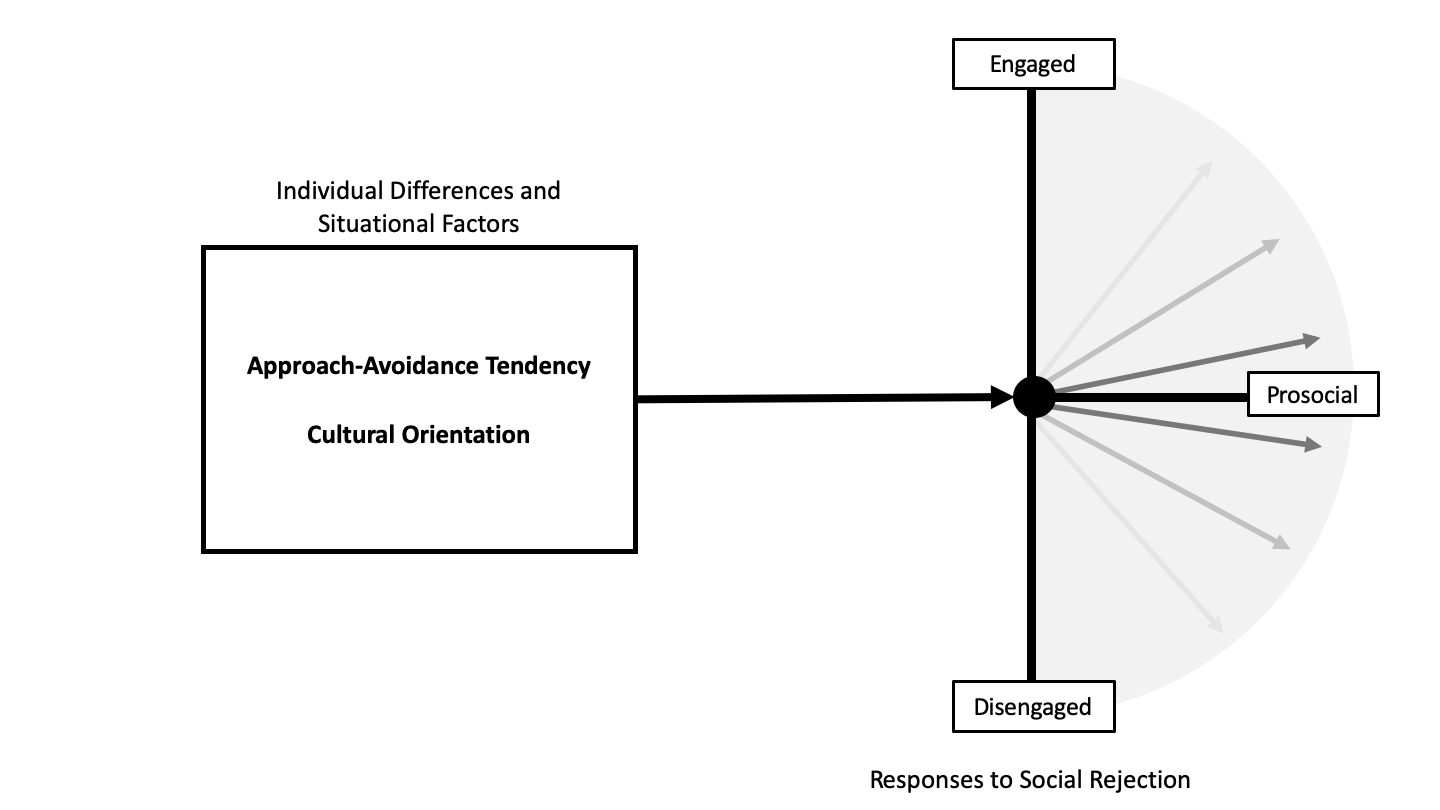

2.5 Using the Bi-Dimensional Rejection Taxonomy to Frame Existing Research

The bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy provides researchers with a more nuanced and accurate understanding of responses to rejection. Previously, researchers were constrained to conclude that certain individual difference or situational factors caused either antisocial or prosocial behavior following rejection, without the appropriate language for specifying the type of antisocial or prosocial behavior being displayed. In this section, we view past research within the new lens of the taxonomy to look for individual differences and situational factors that appear to predict variation along the engaged–disengaged y-axis. In doing so, we make inferences about the y-axis post-hoc based on the available evidence, since the y-axis was not a part of the lexicon at the time those studies were conducted. We omit factors exclusively predicting variation along the antisocial–prosocial x-axis, such as need fortification (e.g., Williams 2009), because they have been extensively discussed elsewhere (Leary, Twenge, and Quinlivan 2006; Richman and Leary 2009; Williams 2009). We divide this section into two parts. The first part focuses on variation in engaged and disengaged antisocial responses, and the second focuses on variation in engaged and disengaged prosocial responses.

2.6 Using the Bi-Dimensional Rejection Taxonomy to Inspire New and More Accurate Hypotheses

As we highlight throughout the paper, the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy is an important advancement to the rejection literature because it helps researchers generate more nuanced and accurate hypotheses and prevents inaccurate conclusions. The taxonomy draws on available theories to make predictions about which individual and situational characteristics will predict when people will respond in one way or another. In doing so, the taxonomy allows researchers to generate innovative hypothesis incorporating all possible response options. In this section, we discuss how the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy inspires new directions for future research. In contrast to the previous sections that demonstrated how existing evidence could be viewed through the lens of the taxonomy, this section purposefully highlights more speculative and innovative avenues for new research that have yet to be tested. Thus, the reader should take these future directions with a grain of salt; they are meant to inspire new and exciting ways to apply the taxonomy.

2.6.1 Spontaneous Reactions to Rejection

Past rejection studies relied on laboratory experiments where behavioral and self-reported response options were constrained. For example, in the hot-sauce paradigm, participants had no choice but to allocate some amount of hot sauce to a stranger without an option to respond differently (Lieberman, Solomon, Greenberg, & McGregor, 1999). Questions remain as to how rejected participants respond in real-life settings where other response options are readily available (e.g., rejected people can watch their favorite TV show, approach a friend, lash out against the perpetrator, or withdraw from others). In addition, people experiencing rejection may use multiple responses simultaneously (e.g., watching favorite TV shows and talking to friends after getting dumped). The existing literature has not investigated which responses people commonly use following rejection in the real world—an important next step to advance the literature. One concrete recommendation is to have at least four types of response options in rejection studies. For example, daily diary or experience sampling studies could assess whether rejection occurred that day, and if so, could ask how the participant responded, ensuring that response options from each quadrant are included.

Without the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy, researchers interested in prosocial responses may inadvertently fail to measure disengaged prosocial responses (e.g., watching a favorite TV program) and may instead solely focus on engaged prosocial responses (e.g., approaching a friend). Doing so brings with it the danger of concluding that prosocial responses do not happen in response to everyday rejection whereas, in reality, they may be happening, but in disengaged rather than engaged manners. Armed with the knowledge of the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy, researchers can now avoid this pitfall and include response options that cover both dimensions.

An unexplored possibility is that people typically react to everyday rejection in disengaged ways (e.g., social surrogacy and social withdrawal). Past research has found that interpersonal rejection is prevalent in everyday life, ranging from subtle ignorance in social situations (e.g., no eye contact and being looked-through) to more obvious ones [e.g., being ignored in conversations, emails, and online messaging; Nezlek et al. (2012)]. People need to regularly cope with these rejection experiences to maintain their belonging. As mentioned earlier, repeated experiences of rejection may promote disengaged responses, particularly in the antisocial domain. We speculate a similar pattern for the prosocial domain—people may use disengaged prosocial responses, rather than engaged prosocial responses for repeated everyday rejection. People can replenish belonging more safely through disengaged prosocial responses because they function to avoid future need threat (i.e., further rejection). The popularity of TV, books, and social media may reflect people’s preference in satisfying belonging from these disengaged prosocial activities, a provocative question for future research.

2.6.2 Neurophysiological Markers

Neurophysiological correlates can provide mechanistic answers about why rejection leads to responses that fall within the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy. Cortisol and testosterone are potentially relevant hormonal markers that can predict rejection responses. The combination of high testosterone and low cortisol levels jointly predict dominance-seeking behaviors, often associated with engaged antisocial behaviors (e.g., physical fights and violence; (Mehta and Josephs 2010; Platje et al. 2015; Romero-MartÃÂnez et al. 2013). When cortisol levels are high, dominance responses are inhibited (and submission responses are facilitated), regardless of testosterone levels. Thus, one unexamined hypothesis is that high testosterone and low cortisol levels may facilitate engaged antisocial responses to rejection. On the other hand, high cortisol levels may inhibit engaged antisocial responses and may instead facilitate disengaged antisocial responses (e.g., social withdrawal and self-neglect).

Considering the interaction between cortisol and testosterone highlights the importance of the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy. If researchers study cortisol and testosterone in the absence of the taxonomy and measure only engaged antisocial responses, they may conclude that cortisol levels do not affect antisocial responses at all. In light of the current taxonomy, this conclusion may be unwarranted—since high cortisol levels should theoretically facilitate disengaged antisocial responses.

2.6.3 Applying the Bi-Dimensional Rejection Taxonomy to Other Threats to Belonging

The bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy offers a blueprint for future researchers who study responses to social stressors that threaten belonging. Currently, the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy is focused on the responses to interpersonal rejection (e.g., feeling uncared for or unloved). But, other social stressors can also threaten belonging, such as separation distress [e.g., feelings of missing someone; Diamond, Hicks, and Otter-Henderson (2008)], death of a close other (Stroebe et al. 1996), and discrimination(Richman and Leary 2009). One interesting application of the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy would be to examine whether responses to these belonging threats also range along the antisocial–prosocial and engaged–disengaged dimensions. Doing so will facilitate a richer understanding of how humans respond to belonging threats.

2.7 Conclusion

Existing theories of interpersonal rejection have exclusively focused on the x-axis, aiming to understand antisocial and prosocial responses to interpersonal rejection. Accumulating evidence suggests a gap in this approach: variability in social responses to rejection cannot solely be explained by the antisocial–prosocial dimension alone. To fill this gap, we propose the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy, consisting of the antisocial–prosocial x-axis and engaged–disengaged y-axis, a novel contribution to the literature. This engaged–disengaged dimension explains variation among prosocial and antisocial responses previously unaccounted for, helps researchers to generate more nuanced and accurate hypotheses about how people respond to rejection, and sheds light on the types of responses that have been understudied in the literature. Thus, the bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy is an important step forward for the rejection literature. Overlooking the engaged–disengaged dimension could result in omnibus hypotheses that lack specificity, leading to erroneous and inaccurate conclusions. The bi-dimensional rejection taxonomy helps researchers to see nuances among responses, better calibrate conclusions, and test novel predictions. With this new map, we can move the literature to new frontiers.

While being denied a desired opportunity (e.g., employment, publication, etc.) is commonly referred to as rejection in lay terms, those types of experiences are outside the scope of this paper because they are not forms of interpersonal rejection; they do not convey to a person that they are uncared for or unloved. Similarly, intergroup rejection (a group excluded by a group) is outside the scope of this paper.↩︎